The Economy - Pakistan's 2020, and Pakistan's 2021

- Land of the Pure

- Mar 13, 2021

- 5 min read

By Myra Ahmed

Pakistan's economy has had its fair share of toil and trouble. Whether that be on the macro scale of massive deficits and debt, or on the micro scale of relentless price hikes, the country and its people have suffered immensely. But a lot of the accountability we place, as citizens, on leaders of the state was lost to 2020's “unprecedented circumstances”. The social, political and economic landscape of Pakistan, along with every other country in the world, was reshaped by the impacts of the pandemic and the measures introduced to curb it, and we did not expect revolutionary reforms or growth. In spite of this, Pakistan's economy has powered through the pandemic much better than most expected it to, and seen a number of very positive reforms setting it up for a prosperous 2021. This week, we dive into Pakistan's 2020, and the outlook for 2021, focusing on the domestic economy on a variety of levels: the current account, economic inequality, women participation, and State Bank reforms. Since there is so much to say (as is the case with most topics concerning Pakistan's domestic and international policies), trade will be discussed at a later date. Let's get started!

Defeating the Deficit

The first and possibly most significant development we saw in 2020 was the eradication of the current account deficit. Pakistan has faced a constant and consistent current account deficit for 17 years, and in effect, this meant that the outflows of foreign currency from the country exceeded the inflows of foreign currency to the country. This resulted in devaluation of the Pakistani Rupee, which in turn, brought inflation. Overhauling the deficit has not been easy, however. One reason for the fall was a reduction in demand for imports amid the pandemic. This can be attributed to the fall in income of the average Pakistani, which meant that there was generally lowered consumption, and with imports being more costly, domestic alternatives were sought instead. Furthermore, remittances to Pakistan reached an all-time high. This was stimulated, primarily, by the general nature of remittances. As ‘shock-absorbers’, they see sharp rises during adverse economic shocks, and this is because family members outside of the country tend to send back a greater proportion of their income to support those at home. Closed off routes in international travel also meant that informal channels of transferring money were no longer available. The Hawala and Hundi networks faced severe disruption, and so, formal channels were employed instead, increasing remittance numbers. To further this, the Roshan Digital Accounts program was launched by the State Bank of Pakistan. The system allows overseas Pakistanis to send money to Pakistan without the complex procedures required by independent banks before it was introduced. As of February 2020, according to Ministry of Information Technology, approximately $500 million have already been deposited into the accounts, and they have seen a consistent increase in monthly deposits since their initiation. However, it is important to note that despite a current account surplus, our trade deficit is still relatively wide. The Express Tribune reported that in January 2020, the deficit stood at $2.15 billion, and by January 2021, this was at $2.6 billion. Our dependence on remittances is dangerous, as despite being relatively consistent, the shocks posed by the COVID-19 pandemic have had unprecedented impacts. A sudden reduction in construction jobs in the GCC, where a huge proportion of Pakistan’s remittances come from, coupled with the resumption of flights and travel across the world allowing for informal channels to take back control, means that remittance inflows can and have seen fall. January 2021 figures show a 6.7% fall from December 2020, indicating this. It is therefore necessary that we continue to diversify our inflows, placing particular emphasis on raising exports through the production of competitive goods, at greatest utlisation of our factors of production.

Via State Bank of Pakistan, Trading Economics

Economic Inequalities

It is also necessary that an emphasis be placed on Pakistan’s economic inequalities. Whether this be by province, by class or by gender, inequities penetrate deep into Pakistan’s economic structure, and this has been exacerbated by the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Restrictions brought in by the pandemic had disproportionate impacts on daily wagers, who make up a huge facet of Pakistan’s labour force. Furthermore, the austerities that have come with the IMF’s support program for Pakistan over the past few years have resulted in skyrocketing inflation, which, once again, has much more significant impact on the poorest in society. In Pakistan, The News has reported figures showing that consumption is three times higher in the top 10% of the population as compared to the bottom 10%, with incomes also showing a five-fold difference. Furthermore, according to the Household Integrated Economic Survey 2018-2019, and as reported by Macro Pakistani, nearly 50% of all consumption expenditure made by low-income Pakistanis is on food. Therefore, food inflation has very significant impacts on them and their quality of life. As a consequence, inequality is widened further. Recent developments do show a positive shift, however, with a current account surplus, we can expect to see revaluation of the currency, reducing the costs of imports and therefore reducing price level.

Empowering our Women

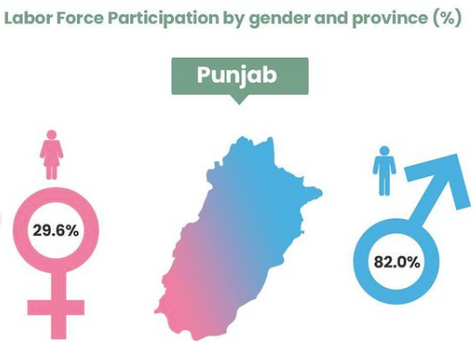

Inequalities have also been seen on the gender front. Despite an equal division in population, Pakistan’s female labour force participation stands at just 22%, according to PBS. This issue is further exacerbated in rural provinces, which are already neglected in economic and social policy. To move forward, it is of utmost importance that these inequalities be addressed so that Pakistan can make full use of its various resources in both capital and labour terms. And the good news is, we are seeing reform. Recent developments by the State Bank, like the Raast banking system, coupled with a greater government emphasis on the need to mobilise women across the country, show progress, and will hopefully result in a better, more equal Pakistan. The benefits of this are widely reported, with increase in female participation being associated with increased productivity. Macro Pakistani reports, that “there is increasing evidence that a woman’s contribution to household incomes leads to decreased illnesses, increased food security, involvement in household decision-making and a future looking focus.”

Via MacroPakistani

SBP Reforms

Raast is also generally an excellent means of stimulating development through digitization and inclusion. Many have described the system to be similar to a government building a road, which then facilitates businesses and consumers on a variety of levels, allowing for innovation, invention and ultimately, growth. A number of other measures to deregulate the business atmosphere, like the revisions made to the foreign exchange legislation, which aims to facilitate exports and start-ups in the country, have also been welcomed across the business stratosphere. All these changes and reforms work in tandem to help Pakistan become a more conductive environment for business and investment, and they surely seem to be delivering results: just last week, our article placed a spotlight on some of Pakistan's biggest start-ups, and 2020's 'Ease of Doing Business' report shows massive improvements, with the country moving up a staggering 28 places in just one year.

Where do we go from here?

It is clear that despite the issues that 2020 brought us, Pakistan powered on, as it always has. We have a long way to go, but the economic progress seen in recent years, on a fundamental, structural level, is a beacon of hope amid these dark times. What we need to see more of, though, is focus. A focus on people, on businesses, and on development. A focus on moving beyond the past, and looking to build a viable economy for the future: one that leads in productivity, in innovation, invention, equality, growth. Pakistan's economic potential is immense, with all four seasons, a well-established agricultural base, and a young population; it is simply about mobilising our factors of production, and placing economic growth over ideological paradigms that have cost the country far too much over the years.

Here’s hoping the reforms we've seen are carried through, and Pakistan’s untapped potential shines through the world in a better, more prosperous 2021.

Adapted from The Consul Magazine, March 2021 Issue

Cover Image via BrandSynario

Comments